Defending and debating the public good of higher education

Over 40 presenters and participants gathered at the UCL Institute of Education, London on Wednesday 27th March to take part in the CGHE Conference ‘The Public Good Role of Higher Education’. The event marked the culmination of an 8-year long CGHE study investigating the public good role of higher education in 10 nations: Chile, Canada, the USA, England, France, Poland, Finland, China, South Korea and Japan. The study comprised 236 interviews with 40 policymakers and 196 university staff from 20 case study universities.

In the conference keynote (view presentation, view text), Professor Simon Marginson elaborated on theories of the public and common good. He highlighted their heightened relevance in the current context of political polarization, war in Ukraine and Gaza, and threats on public welfare and social cohesion. Using the metaphor of the individual tree and the collective wood, he invited participants to defend the integrative, cohesive effects of higher education.

Professor Simon Marginson elaborating on theories of the public and common good

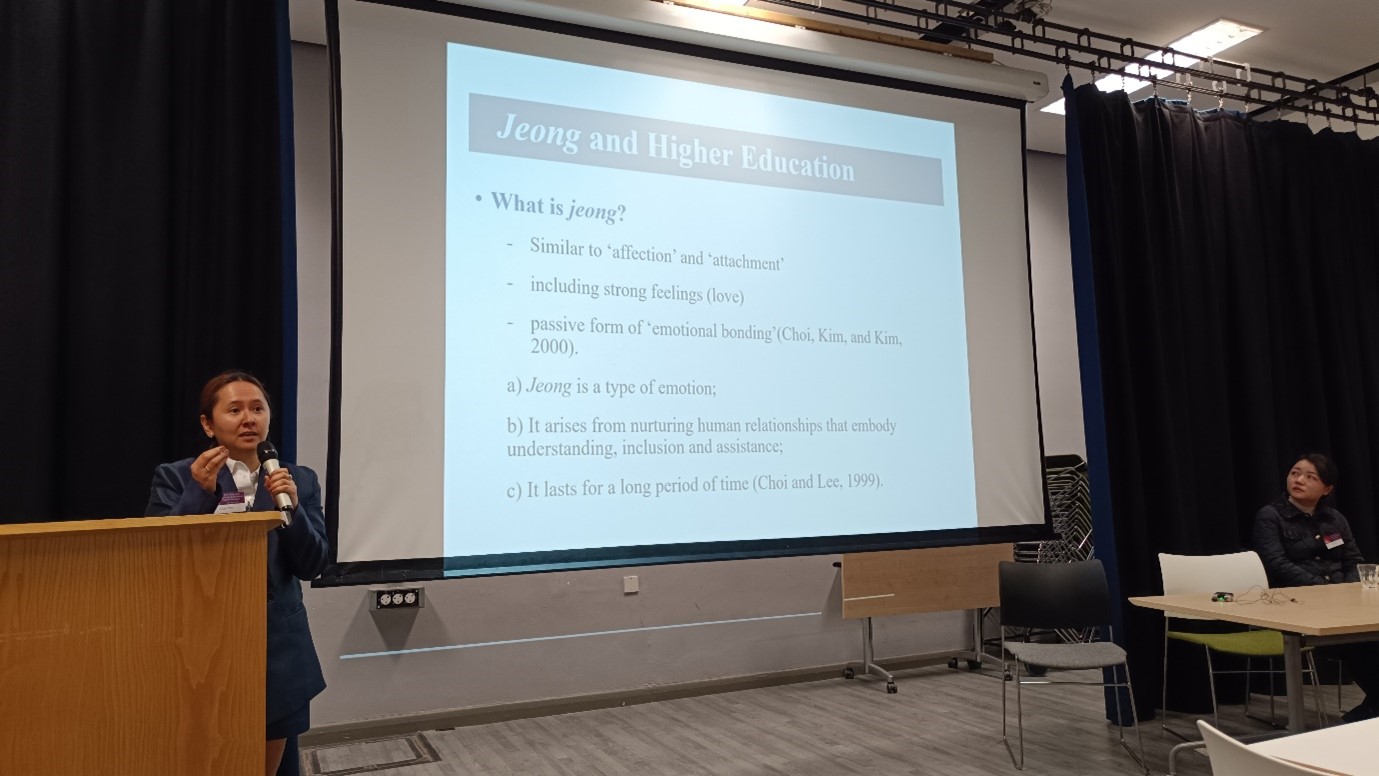

Project members from the 10-nation study then summarised key findings from their qualitative inquiries into local and global public good. The result was a multilingual and multifaceted vision for higher education’s role in public good, covering all three areas of research, teaching and community engagement. For instance, in her presentation on jeong as public good in South Korea, Olga Mun outlined jeong as the basis for humanistic pedagogy, cultivating togetherness, and even human-nature relationships.

Olga Mun outlining jeong as the basis for humanistic pedagogy, cultivating togetherness, and human-nature relationships in her presentation on jeong as public good in South Korea

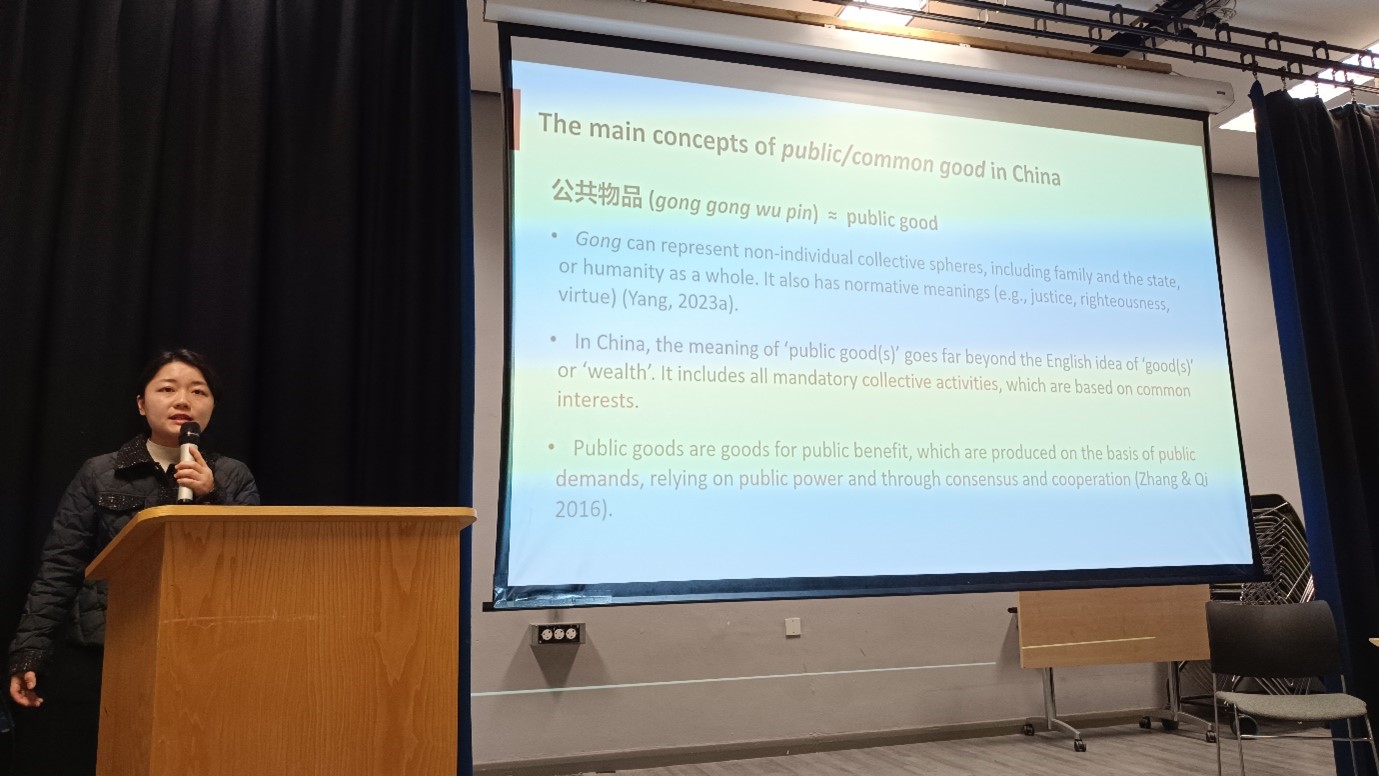

The presentations also highlighted how locally-defined concepts around public/public good can serve as powerful nation-building tools, such as the case of sivistys in Finland, public service and intérêt général in France, and university social responsibility in Chile. The absence of such narratives was noted in the USA, Canada, and England, where neoliberalism has instead pushed a narrow understanding of universities producing private, economic gain. Interestingly, even in countries with a high percentage of private universities like Poland and Japan, interviewees stressed the public and common benefits of higher education. In post-socialist Poland, interviewees tended to express a distrust of the state as facilitator of public good, and instead described a ‘for us, by us’ version of common good. Interviewees from the China and Japan case studies expressed a positive and solidaristic view of global public goods, emphasising the idea of global collective goods as tianxia weigong 天下为公 (China) and stressing the importance of peacebuilding in Asia (Japan).

Lin Tian presenting on the concepts of public common good in China

After hearing the country reports, participants listened to a series of thematic panels and took part in world café discussions to compare similarities and differences between the 10 country case studies and their own context. In the spirit of critical inquiry, they debated the ways that universities produce both public good and public bad.

Participants taking part in world café discussions

The afternoon panel themes covered English higher education policy, practical curriculum interventions, and strategies at the global level to measure global public goods and foster university collaborations in ethical ways. In these discussions, panelists highlighted the importance of applying decolonial perspectives to defining and ‘doing’ public good (Melanie Walker, University of the Free State, and Dorothy Ferary, Universitas Satya Terra Bhinneka).

Dorothy Ferary highlighting the importance of applying decolonial perspectives to defining and ‘doing’ public good

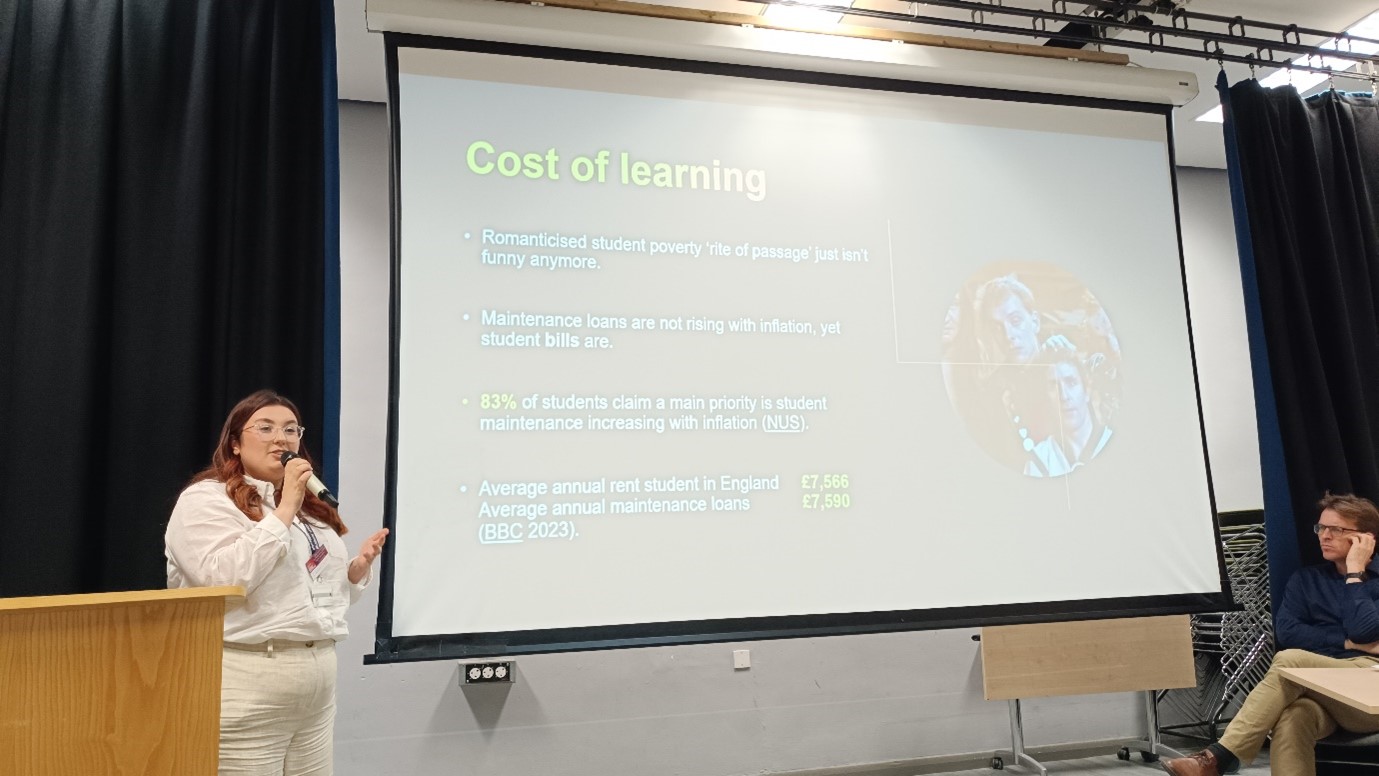

Policy impact also arose as a key concern. Participants in the world café discussions stressed the need for academics to engage with policymakers in direct ways, to use their autonomy to better reward/acknowledge community service work, and to push for sorely needed sector-wide financial support. This point is pertinent given the poverty and mental stress currently being experienced by English university students, a fact highlighted in the panel presentation by Darcie Jones, Vice-President for Education, Plymouth University Students Union. Referring to recent findings from the National Union of Students ‘What Students Think’ survey, she highlighted the inadequacy of current student maintenance support.

Darcie Jones talking about poverty and mental stress experienced by English university students

You can find out more about the CGHE project on higher education and public good on the dedicated CGHE webpage, where a full list of the related book chapters, working papers and journal articles can be found.

The conference organizers would like to thank all the project members, panelists and participants for a stimulating day. In the spirit of jeong, we value the relationships that were cultivated and the seeds of future collaboration that were planted.